By Rowan Salim

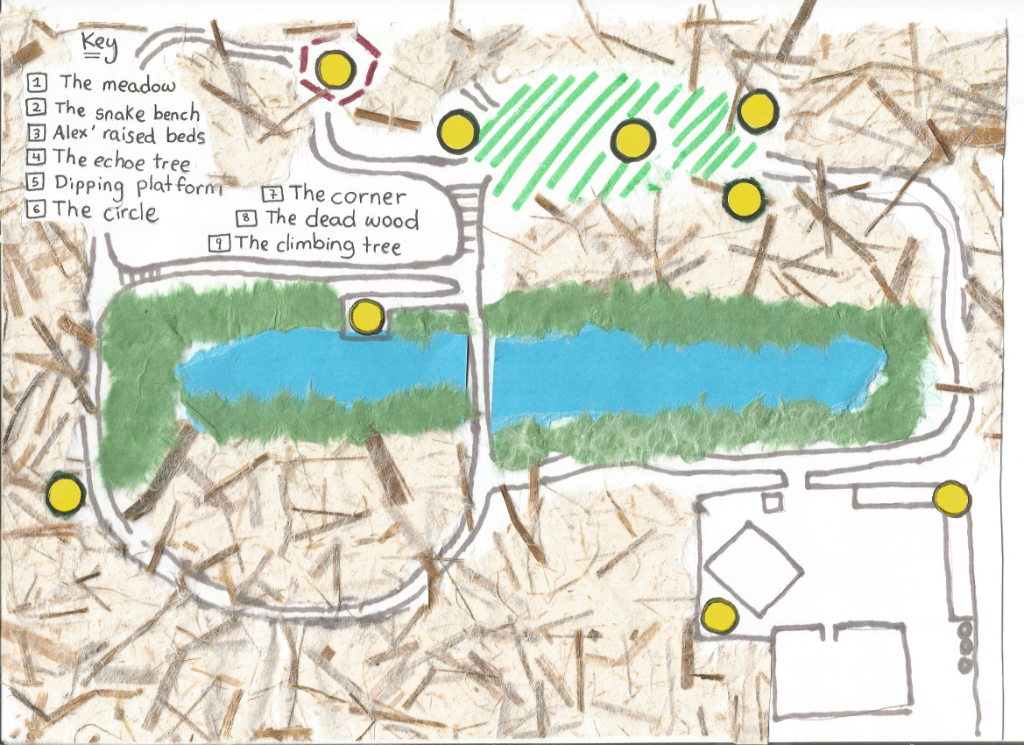

In preparation for the first day at Dacres’ Wood, I made a map to give to the children. The map was a sketch of the reserve made into a puzzle. I had named some of the main landmarks I could see and invited the children to explore the forest and find which is which. I knew at the time that this map would be temporary. That with time and play, names would change, places would morph, and legend would emerge. But little could prepare me for the richness, depth and intricacies of the meaning of place in the children’s world; and I challenge any cartographer to capture the contours of a world which shifts with season and story, dips through dimensions and holds the hand of imagination.

Over the last year, through action, observation, purpose and story, the children have built a memory map of Dacres Wood, lit by experience. Each child’s map is slightly different, as their individual desires, needs, play and presence shape the markers on their landscape. Places have emerged which weren’t there before, and the more the stories of these places are told, understood, retold and embellished, the more meaning and significance they hold in our collective imagination.

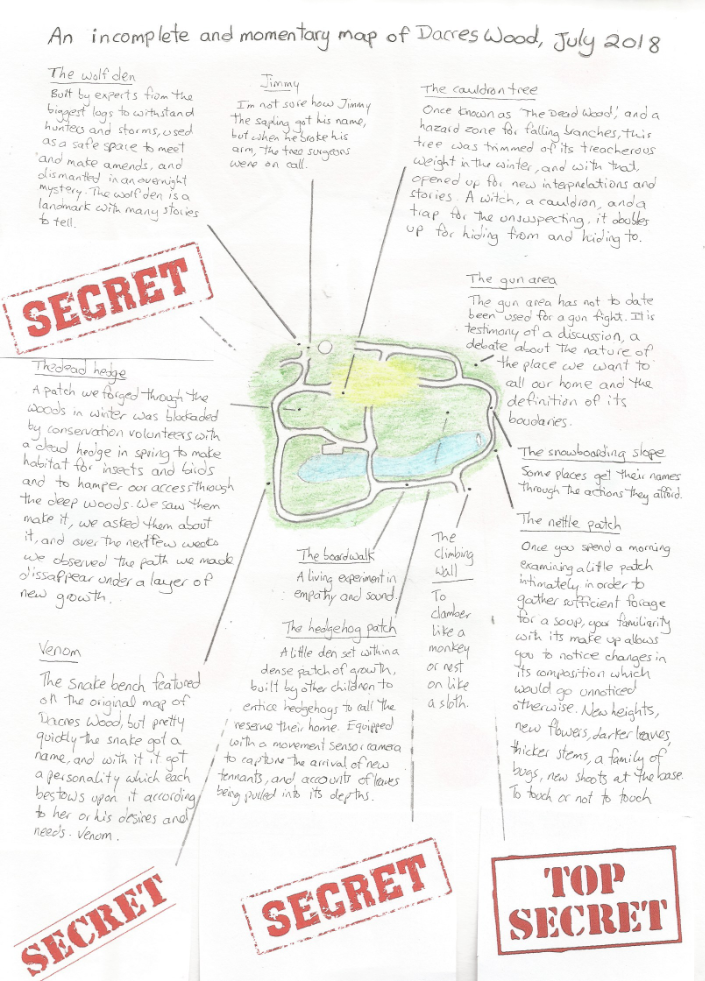

So we learn about Jimmy, the once barely noticed Turkey Oak sapling by the Wolf Den. I’m not sure how Jimmy got his name – that story belongs to the children who were there when he was named – but when he broke his arm, the tree surgeons were at the ready to care for him and support his recovery. The callouses which will surely grow to compartmentalise his wounds will be observed as the seasons roll.

And then there’s The Dead Hedge. A path we forged through the woods in the winter was blockaded by a group of conservation volunteers with a dead hedge in spring to make habitat for insects and birds and to hamper our access through the deep woods. We saw them make it, we asked them about it, and over the next few weeks we observed the path we made disappear under a layer of new growth.

When places have names, it helps them be seen. Dacres Wood Nature Reserve would exist if we didn’t spend time there, and perhaps the wildlife there would be more abundant and more secure without the toing and froing of 11 children and two adults crawling through its underbrush, climbing its trees and yelping out its names. But as the writer, Robert MacFarlane explains, “once (places) go unnamed, they go to some degree unseen. Language deficit leads to attention deficit. As we deplete our ability to name, describe and figure particular aspects of our place, our competence for understanding and imagining possible relationships with non-human nature is correspondingly depleted.”

And in today’s world, it is this relationship with non-human nature which is at risk of loss. And relationships are built on personal experiences which have meaning for the individual. This meaning cannot simply be told, it must be experienced, played and lived, one landmark at a time.

The experiences which give places their names at Dacres Wood do not only relate to the natural world and the ecological processes we witness. Many places also acquire their names through the play, social interactions and contestations which happen in them. Hence, the term ‘boardwalk’ means a lot more to the children at Dacres Wood than a wooden pathway at the edge of the pond. It is an experiment in empathy and sound as the noises we make travelling along the boardwalk resonate in our neighbours’ homes.

The Wolf Den is more than a simple temporary wooden construction, but a magical den where once a mother wolf guarded her young from roaming hunters. It is no surprise then that this space also emerged as a safe space for mediation in our small meetings, to care for each other and make amends. When we arrived one Wednesday morning to find that its mammoth logs and knobbly knots had been mysteriously unravelled and pulled down, it reminded us that our world is not but our own, it is shared with other users, with their own stories. To protect it, we must listen out for the others and communicate with them.

When we look across a landscape, we look for landmarks. Features which have meaning in the past, present or future. Meaning signifies power and possibility, both of which come from story, told or to be told. And with meaning comes belonging, care and purpose.

Free We Grow at Dacres Wood is in part a function of the relationship between a group of children and the place that they’re in. It’s hard, today, to imagine the project anywhere else; but the learning we’re forging from navigating the space and the relationships can be applied as we grow and come to occupy new places in our world.

A geographer at heart, I couldn’t resist taking on my own challenge of mapping our Dacres Wood today. I drew a map and marked on it some of the main sites which had been named and which I felt had had meaning for us this year. As I drew it, I felt a little bit like one of the creators of the Maraudor’s map in Harry Potter. Though in their case they used a magic spell to hide some of its key features. The sites on this new map are sites which hold personal meaning for each of the children involved. In many ways they feel magical in their own right. Was it up to me to share them beyond our gates?

So I took the map in to Dacres Wood last week and showed it to the children in the meeting and told them what I was doing. Firstly of course, they informed me that there were many other sites which I’d missed. And then they listed the landmarks which they wanted to keep secret. Each for their own reasons. So here’s our map, at the end of the first year at Dacres’ Wood. I wonder what it will look like next year?

Rowan

Comments are closed.